By Kwame Aidoo

Accra Cultural Week continues with its enlivening package of exhibitions, performances, and dialogues, as its 9th edition organised by Gallery 1957 carries on with celebrating Ghana’s contemporary art scene, by harnessing communal, historical, spatial and environmental awareness and inspirations. This time, the cultural week is showcasing an exciting programme featuring new work by Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, Denyse Gawu-Mensah, Reginald Sylvester II, and Serge Attukwei Clottey. All but the Reginald Sylvester II exhibition (closing on 9th January), are open to the general public until 7th February, 2026.

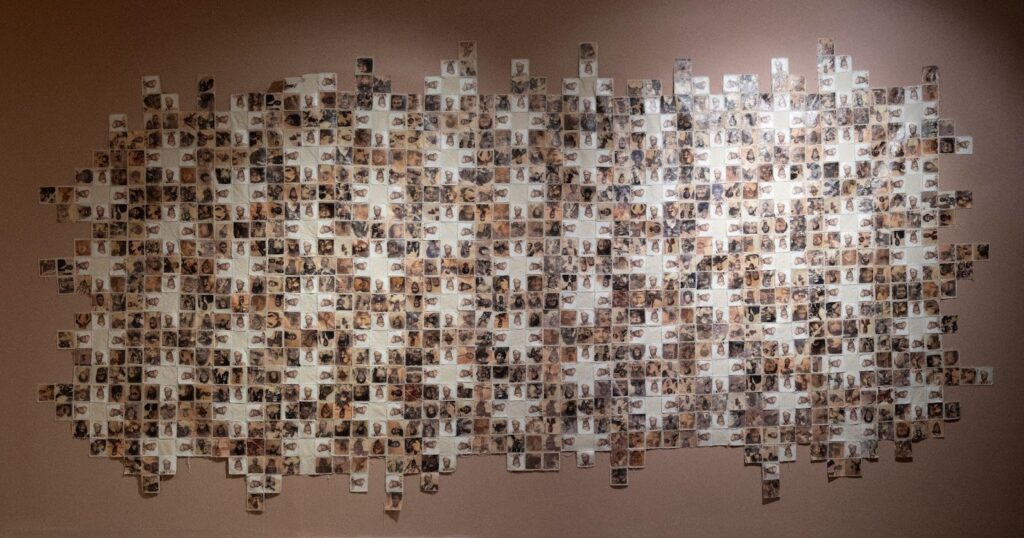

Installation Shot from LIGHTYEARS OF US by Artist, Densye Gawu-Mensah. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

LIGHTYEARS OF US, marks the inaugural solo exhibition by artist Denyse Gawu-Mensah, who was the 2024 winner of the reputed Yaa Asantewaa Art Prize. Curated by Angelica Litta Modignani, Gawu-Mensah primarily draws from her grandfather’s photo album, takes inspiration from the Willis Bell’s archives and other modernist African photo studios, to capture musical, economical, stylish, architectural and social features of post-independent Ghana. By studying the 60s and 70s generation in her family albums, the artist tells “a true story where the idea is not just to focus on family, but to throw light on Ghana”. Gawu-Mensah reflects on domestic Ghanaian households, from about 55 to 65 years ago. From image transfer techniques to digital collage, vintage framing and manual design methods, the artist experiments with diverse artistic modi operandi. A checkerboard tessellation, from a piece titled Nsasawa, meaning an assortment or a blend, is inspired by a type of local Ghanaian textile. Gawu-Mensah’s grandmother used to sew Nsasawa as gifts for family and friends.

The artist therefore makes Nsasawa as a tribute to the matriarch, while referencing her grandfather and his colleagues with a repeated grid pattern of their portraits, forming a mosaic of photos similar to kente abstraction. “It’s a blend of identities from this time,” Gawu-Mensah explains, mapping the significance of post-independent culture. “Music was definitely a way that I wanted to express the time,” Gawu-Mensah confirms, as she describes illustrations of imagined artists signed to a fictional record label. The artist rewrites history to include women artists and bands, to fill in the gaps that history offers.

Installation Shot from LIGHTYEARS OF US, by artist Denyse Gawu-Mensah. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

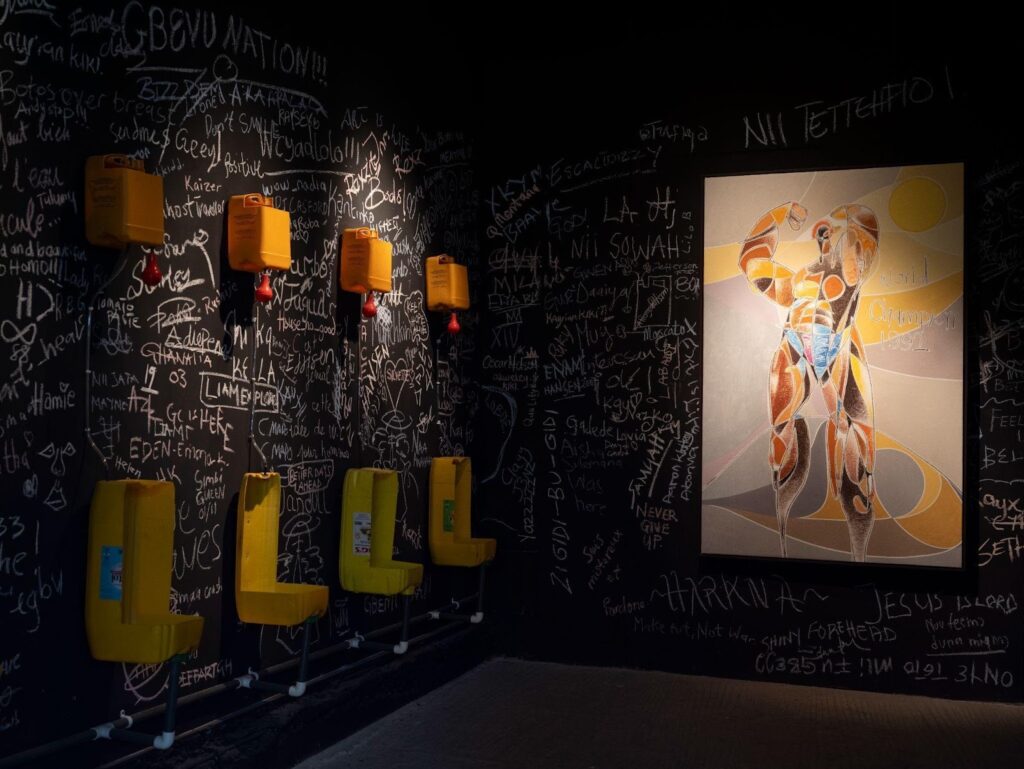

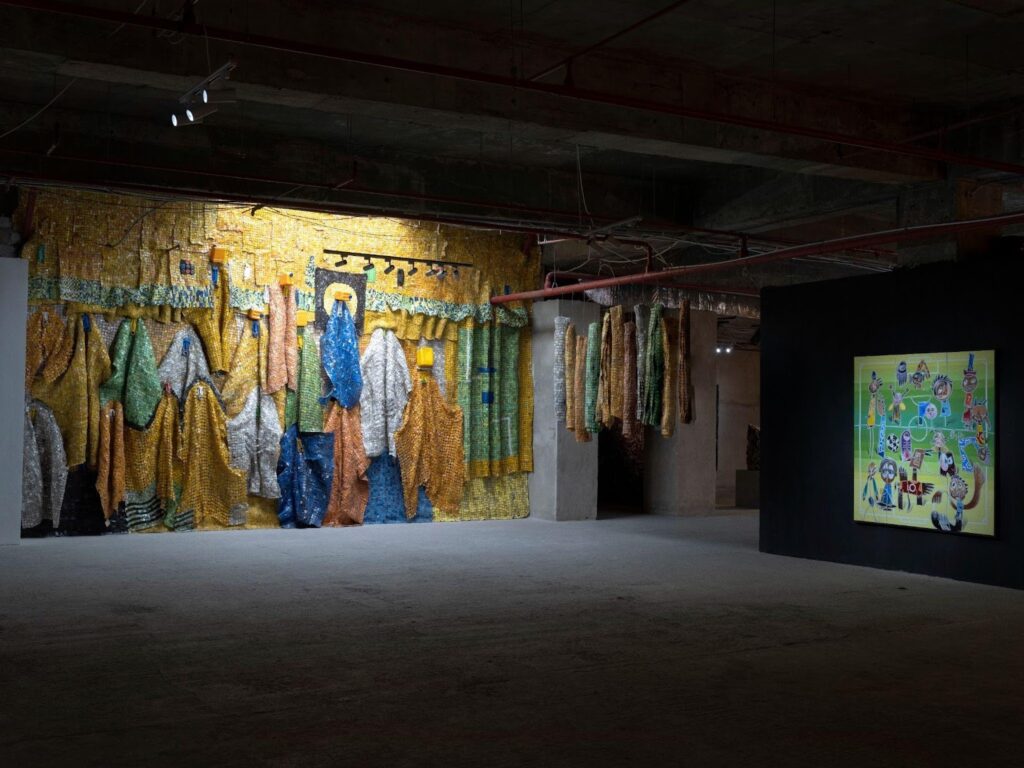

2016 registered Serge Attukwei Clottey at 30, sharing a remarkable debut solo show, My Mother’s Wardrobe, to mark the opening of Gallery 1957, Accra. Clottey is widely known for his application of discarded yellow plastic jerrycans, which are useful in times of water scarcity but become environmental degradation agents after years of serving their function. My Mother’s Wardrobe allowed the artist to assert and foreground his mother’s symbolic expressions, while honouring women’s often-silenced domestic and emotional labour. At Accra Cultural Week, Clottey again positions communal features as central, by pouring not just his art, but ritual expressions of community into Gallery 1957’s 1,400 sqm space. [Dis]Appearing Rituals: An Open Lab of Now for Tomorrow, co-curated by Allotey Bruce-Konuah and Ato Annan, opens a way for the artist to collapse time, by summoning objects which are more likely from a futuristic realm into the present.

Installation Shot from [Dis]Appearing Rituals: An Open Lab of Now for Tomorrow, by Serge Attukwei Clottey. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

Installation Shot from [Dis]Appearing Rituals: An Open Lab of Now for Tomorrow, by Serge Attukwei Clottey. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

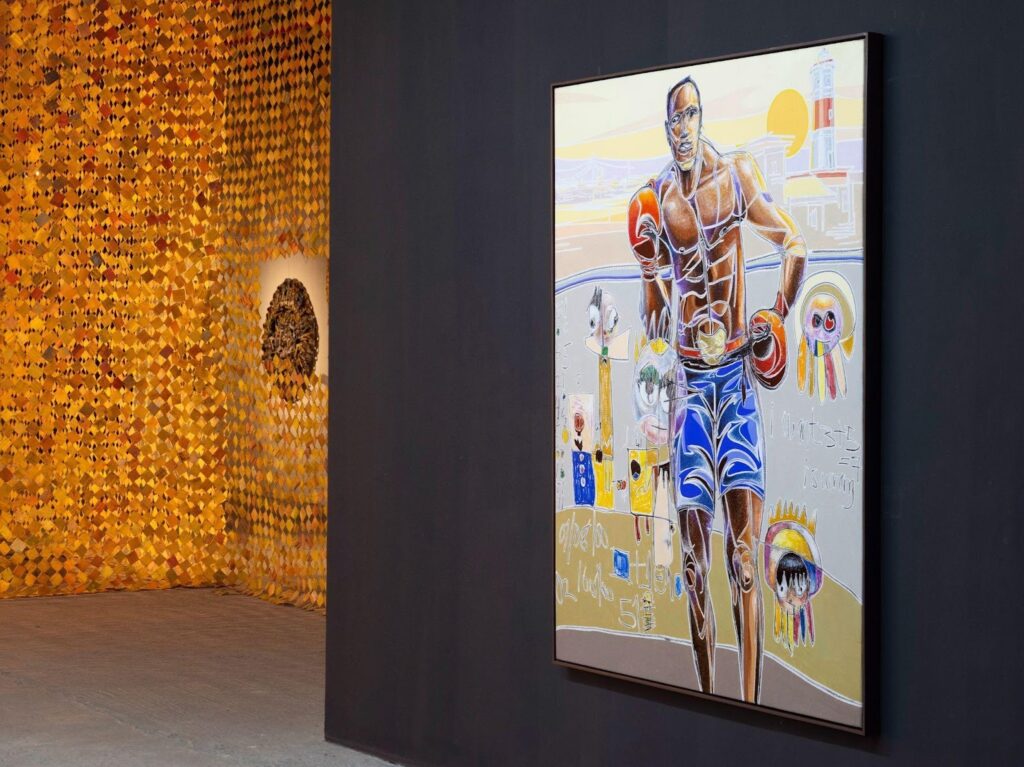

In Clottey’s work, the gently gentrified coastal Accra localities, especially Jamestown, brings in the inspiration that playfully enforce immersive multidisciplinary compositions between collective human intervention and installed pieces. Whether by cutting, stitching, burning and layering found gallons with copper wires, or by inviting modernist rituals of sketch making on canvas, or even by costuming and animating life-sized cubes with fishermen nets or corrugated roof kiosks, the artist is seen creating a theatre of possibilities. Household water containers are extended into vast tapestries, interspersed with paintings of imagined community heroes who could be boxers or everyday people. With the curatorial design choices, one is accorded the feeling of walking into a labyrinth of Jamestown compound housing extending to the freedom of ocean life. With an Afrogallonism performance to cap it off, life becomes culturally layered and shared as sculptures made from wooden boat planks with local visual markings and salvaged street posters with Ga Maamli font are illuminated by kerosene lamps. Sound and scent map relationships, embodying communal resilience as history is boldly shifted forward.

Installation Shot from [Dis]Appearing Rituals: An Open Lab of Now for Tomorrow, by Serge Attukwei Clottey. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

Installation Shot from [Dis]Appearing Rituals: An Open Lab of Now for Tomorrow, by Serge Attukwei Clottey. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

Additionally, Limbo Museum’s On the Other Side of Languish, a solo exhibition by New York–based artist Reginald Sylvester II engages the viewer bodily and spatially. The Other Side of Languish, recently named as one of Frieze’s Top Ten Shows of 2025 consists of hybrid spatial explorations tending to interior-exterior contexts. Limbo Museum, directed by Dominique Petit Frère, is one of Ghana’s newest and artistically probing art and architecture destinations- an “uncompleted” brutalist structure, which used to be an abandoned University of Ghana premise. In partnership with Gallery 1957 and under the curatorial leadership of Diallo Simon Ponte, Sylvester II, after a six-week residency in Accra with support from Joseph Awumee of blaxTARLINES, transforms industrial elements like rubber, aluminum, and steel into minimalist objects that look like they were made in direct response to the location. The large-scale, site-responsive installation features 19 sculptures and 7 paintings.

Installation Shot from On the Other Side of Languish, by Reginald Sylvester II. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

Where the Waters Meet, is a solo exhibition and artistic homecoming by the 1988 Accra-born Portland-based Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. The artist who is renowned for his collaboration with the global fashion powerhouse Zara, is also an Accra Cultural Week highlight. Growing up in Dansoman, a coastal neighborhood in Accra, Kye Quaicoe’s early formative life was shaped by vibrant youthful circulations and the fragile relationship between community and environment. The artist maintains clear memories of collective sense of belonging, and self-curates Where the Waters Meet to create space for reclaiming the shoreline or pool as a space of freedom, rest, and unbothered existence. Moving between memory and imagination, the exhibition resists histories of exclusion and propaganda around Black people’s water recreation realities, offering water as a site of ease, acceptance, and quiet liberation.

Installation Shot from Where the Waters Meet, by Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

By complimenting fine and thick tones with smooth and coarse textures on brilliantly pigmented canvases, Where the Waters Meet, allows the artist to meditate on his contrasting experiences as a resident of the US, where he is in “constant work mode”, with that of Ghana, where he can “rest and spend time with family and friends swimming and surfing”. The artist uses a painting of a diver in a gesture of trust, freedom, and surrender, visually depicted with stretched out arms and body in suspension to connote “the readiness to jump into whatever is ahead”.

Installation Shot from Where the Waters Meet, by Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

In Intermission II, a young woman sits by a pool with a drink and an open book, claiming leisure and interest in knowledge acquisition as private and radical acts. “She is a writer drawn to water, manoeuvring in a community where she is now calling home. The character is a friend who writes about Black people with natural hair, loving their skin, and identities,” Kye Quaicoe narrates. The exhibition’s title, Where the Waters Meet, recalls the Atlantic by way of the Gulf of Guinea as a connection and pipeline between Ghana and the diaspora. For Kye Quaicoe, this becomes the very space for unlearning histories of rupture, while diving into possibilities of reconnection.

Installation Shot from Where the Waters Meet, by Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe. Photo courtesy: Nii Odzenma for Gallery 1957.

With guided studio visits, expansive and diverse exhibition-making that take community into account and artist dialogues, Accra Cultural Week is a platform for critical engagement with access to uncovering an ever evolving African and diasporal contemporary art landscape. The first dedicated art prize for Ghanaian women artists, the Yaa Asantewaa Art Prize opens its fifth edition for public application as Accra Cultural Week continues.

By highlighting historical reflection, communal care and environmental awareness, Accra Cultural Week proves as a sustainable platform for artists and cultural practitioners, while fostering connections between the local community and international groups. Accra Cultural Week mainly promotes Ghanaian and West African art, meaning it attracts a broad audience including local Ghanaians, international collectors, and the diaspora. For stakeholders, Accra’s vibrant scene consistently evinces the importance of culture as both a public good, which should be mirrored in policy priorities.

Editor’s Note

The Accra Cultural Week continues to affirm the power of art to highlight ecological consciousness, underline a sense of belonging and allow us reflect on history, while connecting communities across generations. In this article, writer and curator Kwame Aidoo offers a panoramic view of the Week’s exhibitions—where the politics of water as a recreational resource, rituals of repurposing the ordinary in community, ancestral gatherings in today’s dynamic archive, and spatial explorations converge in bold, contemporary expressions.

As CfCA continues to advocate for 1% of national budgets for culture, stories like this remind us that public investment in cultural infrastructure is not just about venues and funding—it’s about preserving the stories, spaces, and practices that make us who we are.

Kwame Aidoo is a Ghanaian curator, writer, and researcher working at the intersection of memory, architecture, and Black cultural expression. His work explores how artistic and spatial practices can offer new narratives around history, belonging, and diasporic connections. He is based between Accra and the wider Pan-African art world.