This reflection is rooted in personal memory but speaks to a larger truth: that for generations, African women have invested in culture—not only as tradition, but as protection, inheritance, and empowerment. In revisiting the practice of gifting gold, this piece invites us to see culture as a quiet yet powerful form of agency. At a time when access to creative and cultural industries remains unequal, especially for women and youth, stories like this remind us why investing in culture is essential. It is not just about preserving heritage—it is about enabling futures.

Gold as a Domain for Female Agency

I was maybe twelve. I had just fasted my first Ramadan. It was summer, and there was no school. My body was changing in ways I didn’t yet understand. The days were long and slow, and when my friend came to call me to go play outside, I invited her in instead. We sat and drank milk with coffee, and talked instead of playing. That summer, my grandmother called me to sit beside her under the giant fig tree she had planted herself. Her cane rested beside her. She wore a ring I had traced with my eyes a thousand times but had never touched. That day, she slid it off her finger and onto mine. I caressed it with my hands. It was too big, but she didn’t seem to care. She said, “You’re growing to be a woman. You should start wearing gold.” I didn’t ask why. I didn’t think of it as a ceremony. I didn’t know how to act. I was just thrilled that finally, I became like my mother, like my aunties, like all the women around me who wore gold.

In our family, and in many other families in my hometown, this is how it begins. When a girl starts to look like a woman when her walk changes and she forgets how to move in this unfamiliar body she receives her first piece of gold. Usually, it’s the grandmother who passes down a bangle or a golden coin, or the mother who gives a necklace. Sometimes, the father buys a new piece for his daughter. It wasn’t a ceremony. It was just a beautiful ring that made me feel like I belonged to the women I admired.

A close-up of traditional Algerian dowry jewelry, featuring layered chains, coins, and talismanic symbols passed down through generations.

Credit: Source via Google Images

When women here get proposed to, they ask for gold. In some regions the dowry is heavy, ornate, extravagant. In others it’s simpler. But the logic is the same; this is your safety net. When life gets harder you have something to rely on. And It becomes a way for men to compete. He proposes with his offering, like birds flashing their brightest feathers to attract the most desirable mate.

My first understanding of “investment” didn’t come from school. It came in the kitchen, as my aunt unwrapped her bangles and gave them to my father to sell because her husband was sick and she needed money. In Algeria we say: “el hdaid lel chedaid” “metal is for hardship.” And gold is the metal of choice.

It isn’t just jewelry. It’s memory. It’s a plan. It’s knowledge passed from one woman to another, a currency in times when women had none. When land was owned by men, when banks weren’t built for us, when our presence in public life had to be justified, we wore our wealth on our wrists.

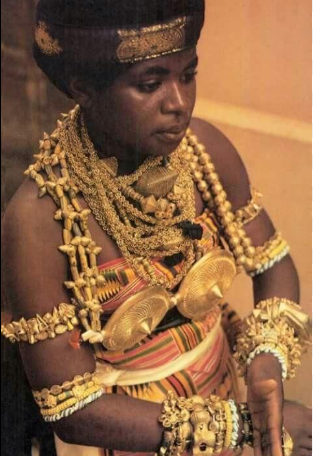

And even now even when we work, when we earn, when we can open our own accounts and buy our own land we grow up as young girls infatuated with gold not just for how it sparkles, but for what it represents. A woman in gold is proud, protected and dignified. From the rich aunties in East Africa to the strong grandmothers of North Africa, gold is a shared language across the African continent, In West Africa, particularly among the Akan of Ghana, gold jewelry was historically used as a symbol of royalty and spiritual strength many women were gifted gold weights as part of their dowry or rites of passage.

A Ghanaian woman dressed in royal regalia featuring Akan gold weights and symbols of status, spiritual strength, and inheritance.

Credit: Source via Google Images

In Ethiopia, ornate gold earrings and necklaces signify both beauty and belonging, often passed down through the maternal line. In Tuareg and Amazigh communities of North Africa, silver and gold jewellery functioned not only as decoration but also as movable wealth an insurance policy that women could rely on independently of men. These pieces often contain inscriptions, talismans, or specific shapes believed to protect from evil or misfortune, so this adornment becomes both spiritual and economic survival. and yet this practice has no name. Like so many acts of female solidarity, it is unseen, unrecognized and uncelebrated.

But we still give it to our daughters. We still pass it down.

As the first inheritance.

The first whisper of agency.

The first thing you own that no one else can take.

You can wear it, hide it, melt it if you must.

Gold is the quiet insurance policy women give each other, wrapped in love, passed in silence.

When I look back, I realize I’ve always been surrounded by quiet revolutionaries.

Their bracelets clink like bells. Their rings shine like reminders. Their necklaces tell stories.

Their lessons came with afternoon coffee and unspoken promises: you will be okay.

Women had no weapons to fight , so they gave each other small armors.

And I carry their lessons with me now.

Because women have always found ways to fight back.

Even those who never called it that.

Editor’s Note

This reflective piece by Benyaiche Nesrine, a writer and content creator from Algeria—offers a deeply personal and culturally rich exploration of gold as a symbol of womanhood, memory, and agency.

With a Master’s degree in Physical Activities and Sports, and a career as a physical education teacher, her writing draws on lived experience and academic insight to explore themes of identity, ecology, and everyday politics in North Africa. She is also the co-founder of GaïaTech, an ecofeminist initiative that connects Algerian women to green tech and sustainability, and an alumna of L’École Féministe and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

In this piece, Nesrine traces how gold—passed quietly between generations of women—served as both adornment and financial protection, long before formal economic inclusion was possible.

Her story reminds us that culture has always been a form of empowerment—especially for women.

Sources

For African Art. Akan Goldweights: An African Artform with Meaning. Retrieved from: https://forafricanart.com/akan-goldweights/

Wikiwand. Jewellery of the Berber Cultures. Retrieved from: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Jewellery_of_the_Berber_cultures

Bedouin Silver. What is Dowry Jewellery? Retrieved from: https://bedouinsilver.com/what-is-dowry-jewellery/

Adastra Jewelry. Exploring the Rich Heritage of Ethiopian Jewelry. Retrieved from: https://adastrajewelry.com/blog/exploring-the-rich-heritage-of-ethiopian-jewelry